Antidotes to Purpose-Induced Eye-Rolling

A Purposeful Rethink

Simon Sinek’s Start With Why TED Talk has over 60 million views. That’s serious traction.

The idea that purpose fuels motivation and performance? It basically makes sense. Knowing why you get out of bed matters.

But lately, we’ve been wondering: is Start With Why hitting diminishing returns?

There’s a loyal fanbase—true believers who swear by it—but it’s starting to feel a bit like CrossFit or crypto: for every die-hard evangelist, there’s someone quietly backing away, muttering, “Not for me!”

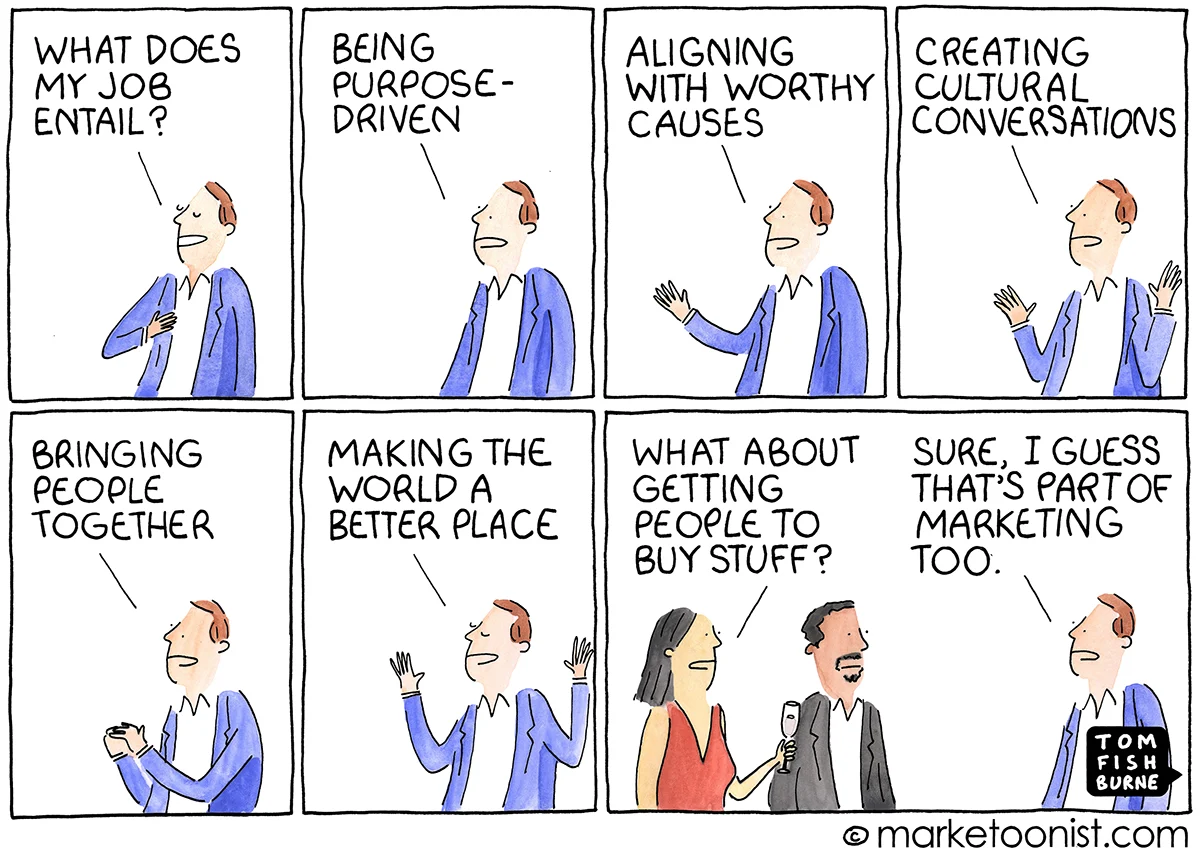

We’ve heard a range of critiques. Some say it encourages navel-gazing. Others feel it’s been co-opted as clever branding. Here’s one eloquent critique.

And we’ve found ourselves asking questions. Our own team development tool starts with why-type questions. But as we’ve refined it, we’ve started thinking harder about the language we use—and the expectations we set.

So this is a check-in. Is it time to rethink how we talk about purpose at work?

When “Purpose” Starts to Backfire

The word purpose used to feel fresh. Now, for some, it lands with a sigh.

Let’s face it: just saying the word “purpose” can prompt eye-rolls with some. It might be seen as turning corporate life into Top Gun—all swaggering missions and world-changing heroics—all be it - with fewer fighter jets and more biscuits.

Meanwhile, many people are simply trying to get through the week. They want to do good work, feel it matters, and maybe get home in time for dinner. Not everyone’s in the mood to scale Maslow’s pyramid before their morning coffee.

And that’s okay.

The risk is that purpose becomes performative. Like there’s a secret club of “enlightened employees,” and you missed the invite.

The phrase “start with why?” can be misleading. Finding what really matters in your work is rarely neat. It’s slow. Often messy. And sometimes, it doesn’t look like “purpose” at all—it just feels like doing something well.

So how do we hold onto the value of purpose, without layering on pressure or fluff?

Why Words Matter

Language isn’t neutral. It shapes what we see—and what we don’t.

Take Gwyneth Paltrow. When she described her divorce as a “conscious uncoupling,” the internet lit up. The story wasn’t the event—it was the frame. Same facts, different impact.

A 1969 football match between El Salvador and Honduras escalated into armed conflict—partly stoked by media describing migrants as “invaders” and “plagues.” Words didn’t just report reality. They inflamed it.

In short: language doesn’t just describe - language directs.

So maybe the question isn’t whether purpose matters. Maybe it’s: how are we framing it?

The Three Layers of Purpose

We’ve found it helpful to think of purpose in three layers:

- Organisational Purpose – the official mission, usually captured in a statement

- Team Purpose – the shared focus or goals of a group

- Personal Purpose – the individual’s sense of meaning in their work

Each layer is valid. But they’re different. And when we use the same language across all three, things start to blur.

That’s where reframing becomes useful.

Usefulness as a Lower Benchmark

Let’s start with the top: organisational purpose.

Most companies have mission statements. Some are clear. Some are ambitious. Some are… well, this:

“We’re revolutionising human connectivity to unleash limitless potential in the digital workspace.” (Translation: we make conference call software.)

This is when teams start to cringe.

Not because they don’t care — but because they can’t see themselves in it. It’s hard to “check in with the mission” when the mission has floated off into another dimension. One where cereal is a social movement.

It’s not that mission statements are bad. But we’ve overcorrected. In trying to sound meaningful, we’ve made the practical sound ridiculous. And now there’s a weird gap between what we say we do, and what we actually do.

So what if we just... lowered the bar?

Instead of “changing the world,” what if we asked: Are we doing something useful?

“We help people do X, and here’s how.”

Simple. Grounded. Relatable.

In a world of mission statements reaching for the stars, usefulness is a return to earth. It’s a humbler benchmark—but perhaps a more effective one.

Especially when things get tough. During the pandemic, the people we most relied on weren’t armed with vision decks. They were delivery drivers, nurses, sanitation workers. Not glamorous. But undeniably useful.

That moment recalibrated something. We saw, in real time, how clarity and contribution mattered more than lofty words.

And maybe we haven’t forgotten.

The Emotional Test: What the Words Trigger

The true test of a mission statement isn’t how it sounds—it’s how it lands.

When teams hear a mission that’s clear and grounded, they often feel:

- Relieved – “Finally. That makes sense.”

- Reassured – “This actually matters.”

- Motivated – “I know how I contribute.”

But when the mission goes full purpose-industrial-complex?

- Embarrassed – “Are we seriously saying that?”

- Disconnected – “Is that what we think we do?”

- Suspicious – “How much did we pay for this fluff?”

Words matter. And when they misfire, the cost isn’t just confusion—it’s credibility.

From Team Purpose to Team Contribution

Team purpose sessions often begin with Post-its and the question, “Why do we exist?”

And sometimes that works.

But more often, teams aren’t wrestling with existential questions. They’re trying to deliver on goals, collaborate without burnout, and maybe enjoy the odd sandwich.

So here’s a different entry point: What’s our contribution?

Contribution is additive. It links to usefulness. It recognises that teams sit inside systems, not silos.

You might try asking:

- How does our team contribute to the organisation?

- What would make our contribution more valuable?

- Where can we better support other teams?

You don’t need a retreat. Just space for a clear, honest conversation.

From Personal Purpose to Personal Meaning

And then there’s the individual.

This is where things get real—and where purpose lands most naturally.

Not everyone wants work to be their calling. But most people want it to count.

We’ve found that talking about meaning—rather than “purpose”—opens the door. It’s less loaded. More personal. And it makes room for nuance.

The research backs this. A two-year study involving thousands of employees across 14 countries showed that structured reflection on personal meaning—not purpose—had measurable impact:

- 50% reduction in underperformance

- Higher bonuses

- Increased job satisfaction

- More aligned behaviour across teams

- And in one striking outcome, men in the study were significantly more likely to take parental leave—breaking cultural patterns

And all of it came not from telling people what matters—but from helping them remember what already does.

Misalignment

Some people realised their job no longer aligned with what they valued—and they left.

That wasn't a failure. That was clarity. For them, and for the team.

The myth is that everyone needs to be perfectly aligned with the company’s mission. The truth? Most of us just want to feel that what we do isn’t totally at odds with what we believe.

Our relationship with work doesn’t need to be deep, life-defining purpose—but total disconnection? That’s when things unravel. Same with values. It’s less about full agreement, more about recognising when the gap is too wide to ignore.

Tension isn’t always a problem. Sometimes, it’s where the most useful conversations start.

The goal isn’t perfect alignment. It’s enough alignment that the work still feels worth doing.

So, What Now?

We’re not arguing against purpose.

We’re just saying: let’s ease up on the misty-eyed metaphors. Let’s not turn every job into a calling. Let’s use language that people can see themselves in.

Try this:

- Ask if the organisation is useful. Every organisation can be useful—whether in insurance, logistics, creative work, healthcare, or tech.

- Let teams define their contribution. Skip the poetry. Just ask, “What do we add?”

- Give individuals space to reflect on meaning. Quietly. Privately. With time and trust.

And remember: sometimes, the most meaningful thing a team can do isn’t change the world.

It’s taking the rubbish away.

See how TeamPath can transform your team’s performance today